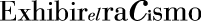

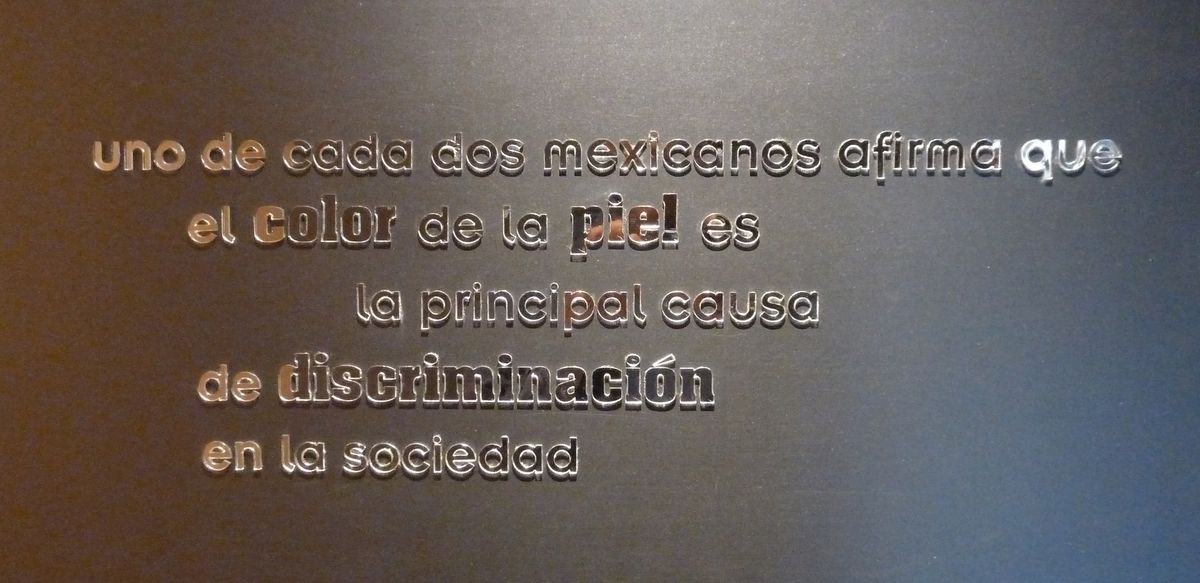

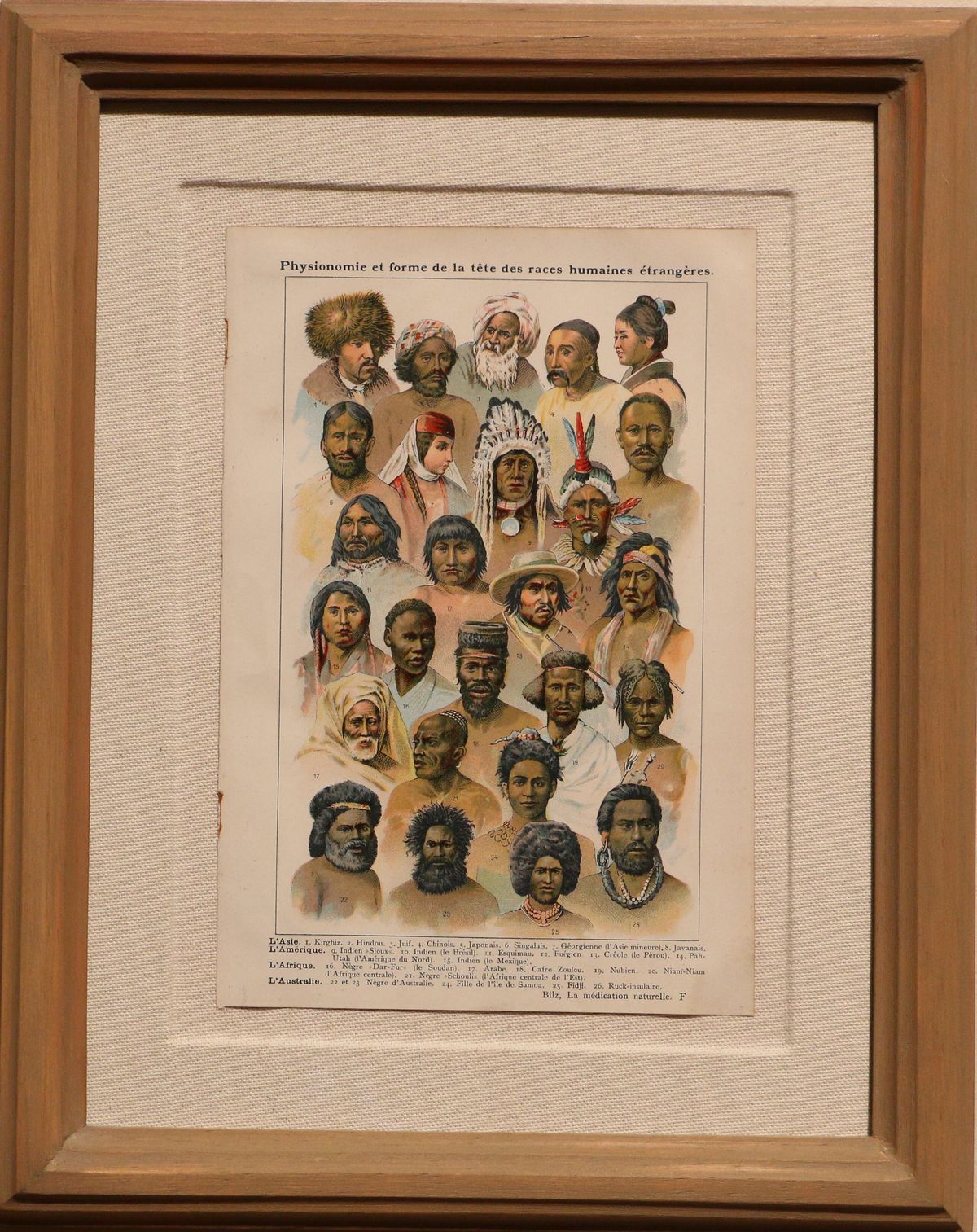

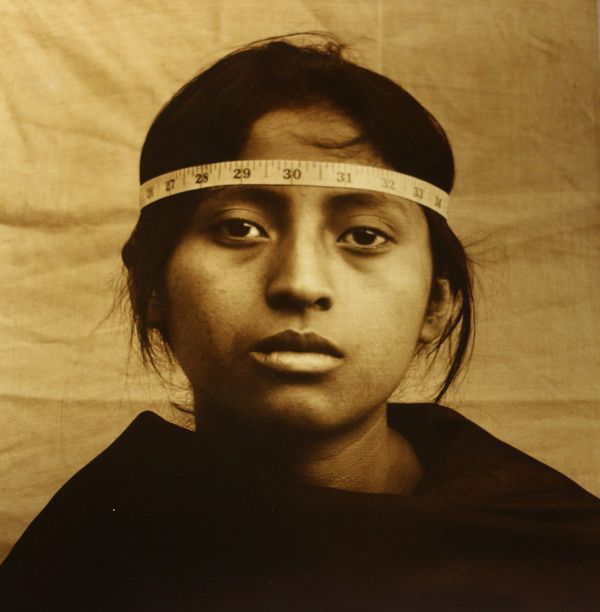

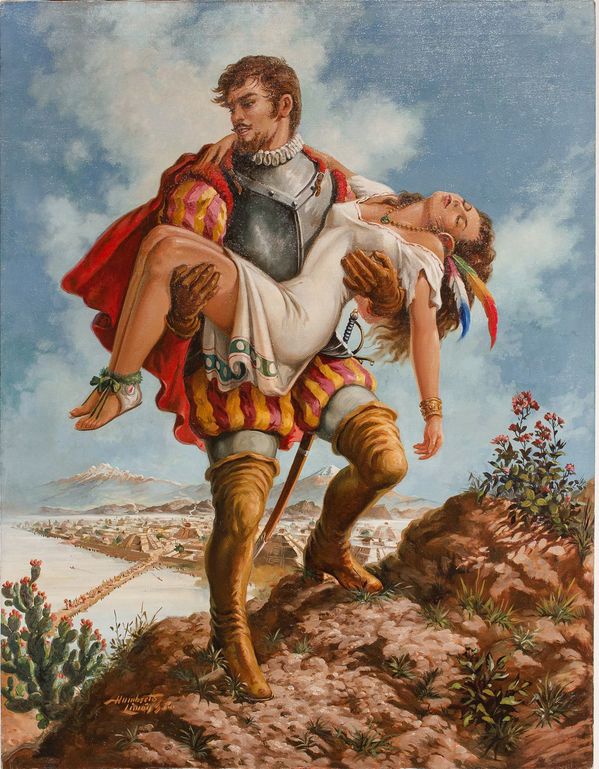

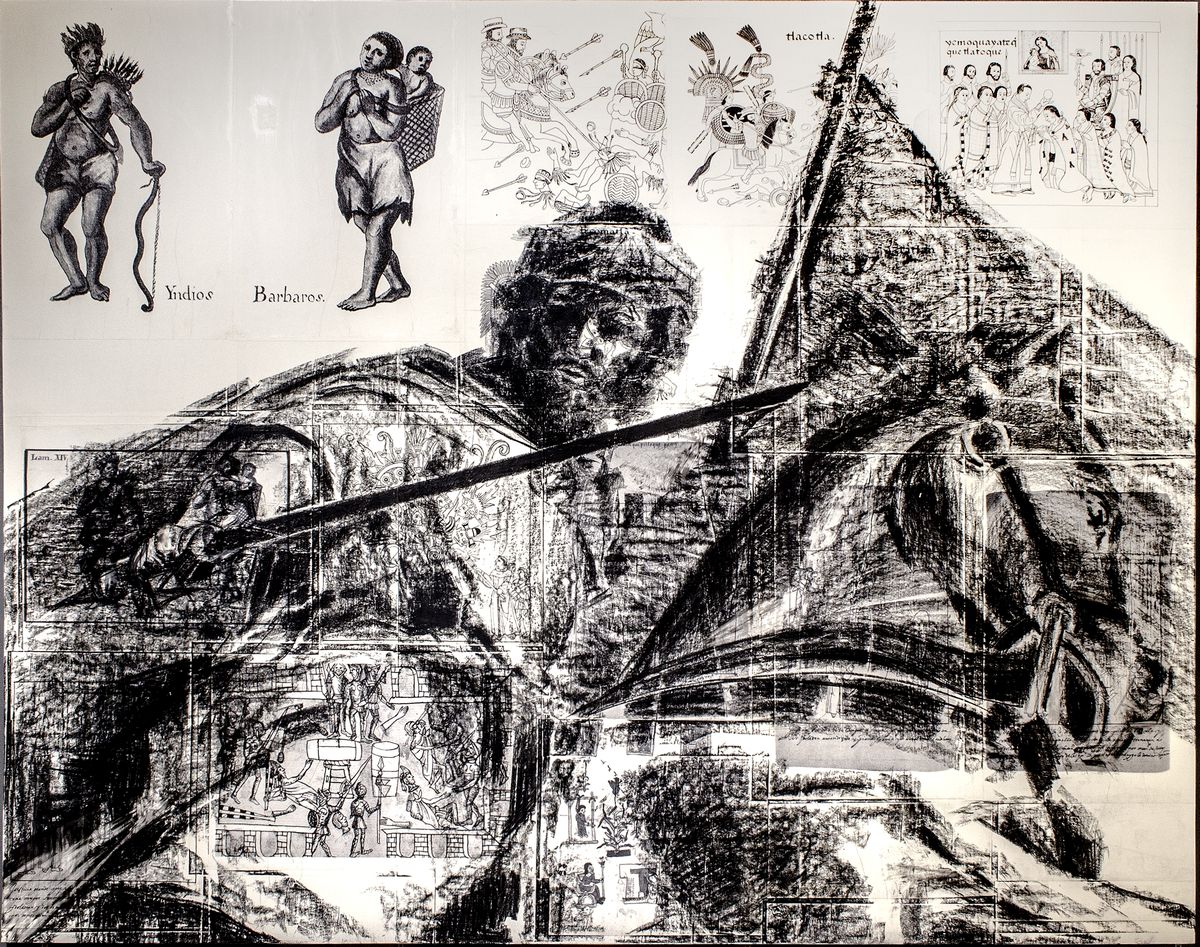

Discrimination due to skin color, physical features and one’s way of speaking and dressing is a fact of daily life in Mexican society, as it is in many other parts of the world. The terms that accompany this discrimination – indio patarrajada, naco, chaca and many others – show how these physical and cultural characteristics are assigned a set of values; that is, it is thought that white skin is better than dark skin, narrow noses better than broad noses and Spanish better than Nahuatl or Maya.

Let’s Talk About Racism, 2016, Video Installation. Idea and text by César Carrillo Trueba. Produced by La Maga Films