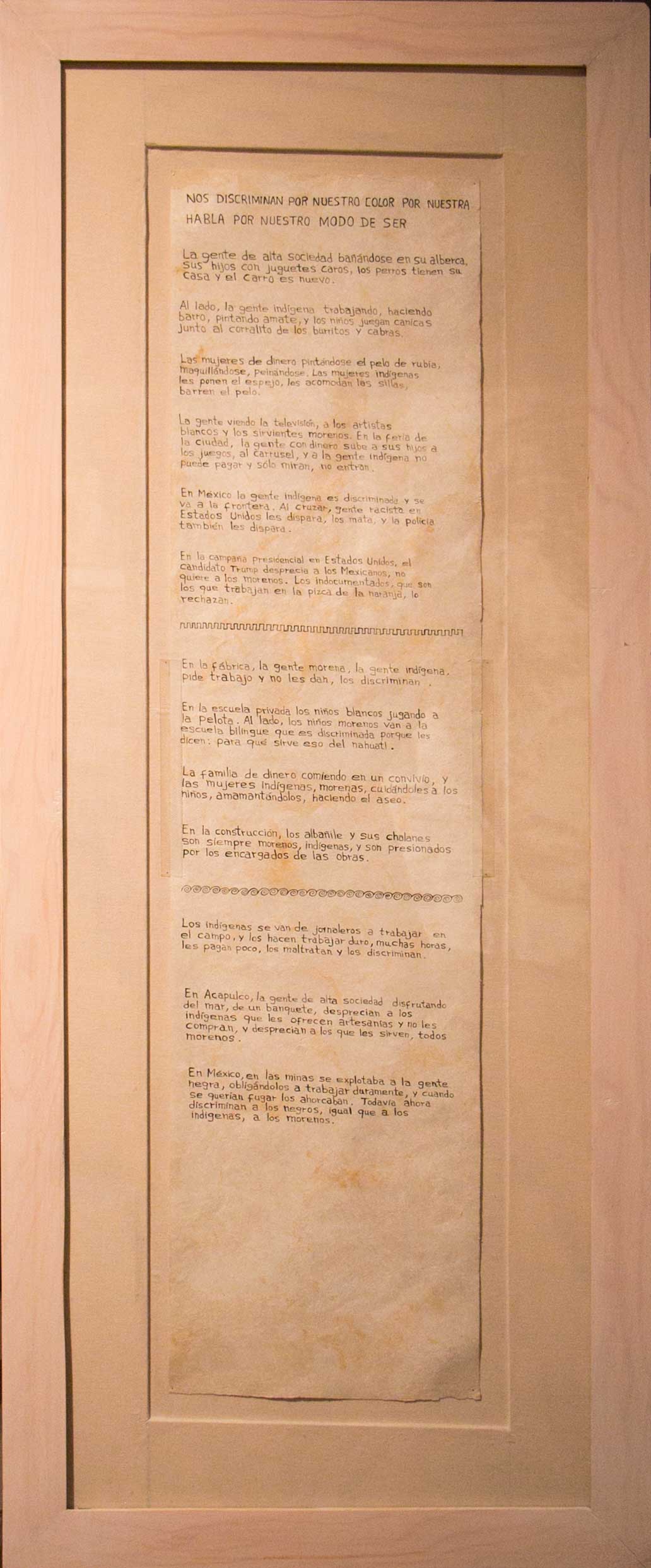

Unknown, Plaza de la Constitución, ca. 1930, Digital Print, Víctor Casasola Archive, SINAFO/INAH Archive, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Unknown, Plaza de la Constitución, ca. 1930, Digital Print, Víctor Casasola Archive, SINAFO/INAH Archive, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

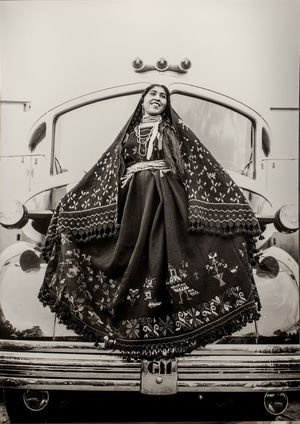

Finding jobs as construction workers, manual laborers, servants, gardeners and newspaper salesmen, recent arrivals to the city created a new urban typology, as occurred in the colonial era with the caste system, reproducing old racist clichés under new forms: the peladito, the naco, the maria and the chacha, among descriptors, and, in the event of a conflict: pinche indio, naca igualada, etc.

Cruces and Campa, ca. 1875, Indian Tortilla-Maker, Cruces and Campa Collection, SINAFO/INAH Archive.

Cruces and Campa, ca. 1875, Indian Tortilla-Maker, Cruces and Campa Collection, SINAFO/INAH Archive.The new residential neighborhoods, built in the image of the United States and designed to be inhabited by people of a single type – the more homogenous they were, the more exclusive they would be – led to the flight of the upper class from the old downtown, replacing a certain sense of coexistence with an unfamiliarity with the other, distrust, suspicion. Segregation is fertile ground for racism and clichés reconfigured themselves and were reproduced in mass culture, television and advertising, sketching the image of an urban mass with an indigenous face, necessary as a labor force and in political campaigns, but undesirable as a neighbor and unworthy of being one’s equal.

The distribution of power: Social segregation is so acute in the city that it regulates consumption, with stores distributed in accordance with the buying power of each area. If a map with skin color was superimposed, the segregation would be equally clear.

As a result, our imaginary of the indigenous contains a variety of figures: the glorious Indian of past civilizations, worthy of showing off to the entire world; the indigenous people who preserve their culture, generally seen to be disappearing despite their numbers (over 15 million), now paternalistically reconsidered as part of “our cultural diversity” but reviled with the worst racial epithets and repressed if they express their discontent and defend their rights; and the city dwellers, the descendants of indigenous people who don’t flaunt their genealogy, the “nacos” and “cara de indios” who are denied equal opportunities because of their appearance and have to work twice as hard to advance, the usual suspects, those receiving unequal treatment before the law and exposed to all manner of abuses, those who should remember “their place” and not be “overfamiliar,” those who suffer an equally cutting racism on a daily basis, but one less visible, affecting millions of people.

Pablo Valtierra, Community of X’oyep, 1998, Digital Print, Cuarto Oscuro Archive.

Pablo Valtierra, Community of X’oyep, 1998, Digital Print, Cuarto Oscuro Archive.

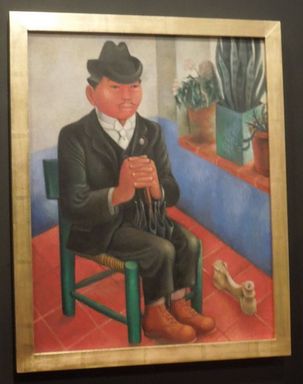

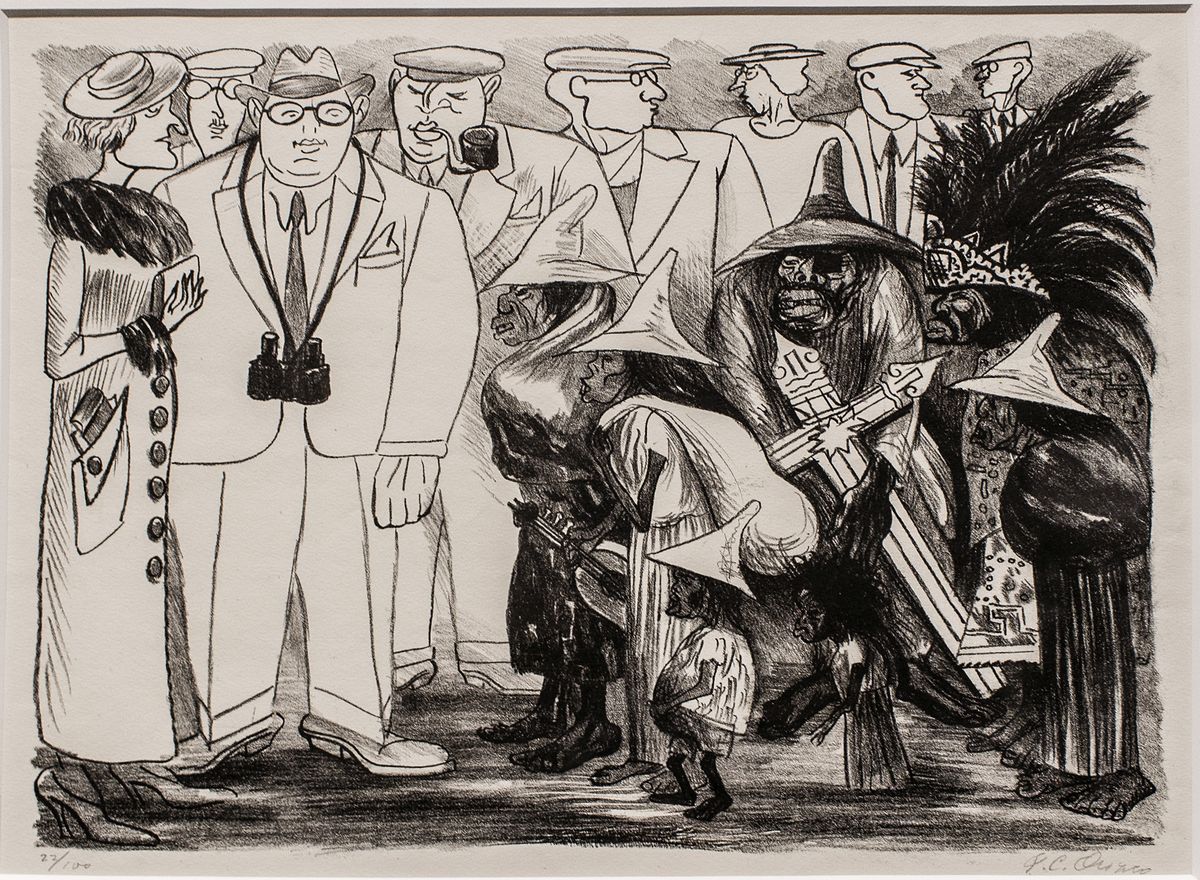

José Clemente Orozco, Tourists and Aztecs, 1935, Lithograph, INBA/MACG Archive.

José Clemente Orozco, Tourists and Aztecs, 1935, Lithograph, INBA/MACG Archive.  Hugo Brehme, Group of Dancers and their Banners, ca. 1915, Paper Closeup (Negative: Silver on Glass), Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Archive.

Hugo Brehme, Group of Dancers and their Banners, ca. 1915, Paper Closeup (Negative: Silver on Glass), Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Archive.

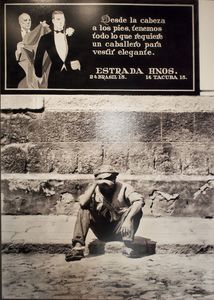

Héctor García, Between Progress and Development, Undated, Silver on Gelatin, María and Héctor García Foundation Collection.

Héctor García, Between Progress and Development, Undated, Silver on Gelatin, María and Héctor García Foundation Collection.  Andrés Audiffred, Let Him Go…The Easy Way! Original Art for a Cover of El Universal Ilustrado, ca. 1930, Colored India Ink and Watercolors on Paper, Carlos Monsivais Collection.

Andrés Audiffred, Let Him Go…The Easy Way! Original Art for a Cover of El Universal Ilustrado, ca. 1930, Colored India Ink and Watercolors on Paper, Carlos Monsivais Collection.

The Other, I, We...

What is it that makes someone who is different than us into “the other”? The gaze, our gaze. Our ways of seeing have an implicit series of preconceived ideas, values and expectations: prejudices. There is no such thing as an innocent gaze. On it depends our relationship with the world, with “the other,” and our language accompanies it and molds it: the expressions we use to describe someone, how we address them.

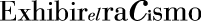

Federico Gama, Mazahuacholoescaopunks, 2007, Color Photographs, Federico Gama Archive.

Federico Gama, Mazahuacholoescaopunks, 2007, Color Photographs, Federico Gama Archive.

In the face of abuse, contempt and other attitudes they face in the city, some young indigenous people have taken on new identities with certain similarities with that of groups that inspire respect and even fear. A strategy of protection, of survival.

Beyond being or not being racist, it is the interiorization of these ideas, expressions and values – including aesthetics – that determines our relationship with “the other,” whether they be of African, Asian, Arab, Jewish, European or indigenous origin, or with some ancestry from any of these groups, which is always difficult to define and delimit. The mere fact of placing someone in a category is due to this (it’s currently very common in many countries for all Arabs to be seen as terrorists). The racist clichés that come up in certain situations, such as when there’s a conflict, are a clear expression of this (“indio igualado,” “pinche naco,” etc.).

The problem doesn’t end there, as “the other” can be a white person in a position of power, in which case we put ourselves in the role of victims – a self-deprecation based on this same interiorization of clichés due to the power of “aspirational” images that, over and over, day after day, insist on the superiority of white skin. Although we can also respond aggressively, as a way of preventing or preempting discrimination.

What’s the point of asking ourselves how Indian our conversation partner is? What’s the point of treating indigenous people with contempt or paternalism? What makes someone believe that their skin is lighter than it really is? Diversity is an intrinsic characteristic of humanity. Equality is another. Equality in diversity is its synthesis, and is basic to coexistence. Changing our gaze and no longer looking at those who are different through the prism of degrading categories can contribute to this. It’s one step towards overcoming this serious problem, here as in the rest of the world.

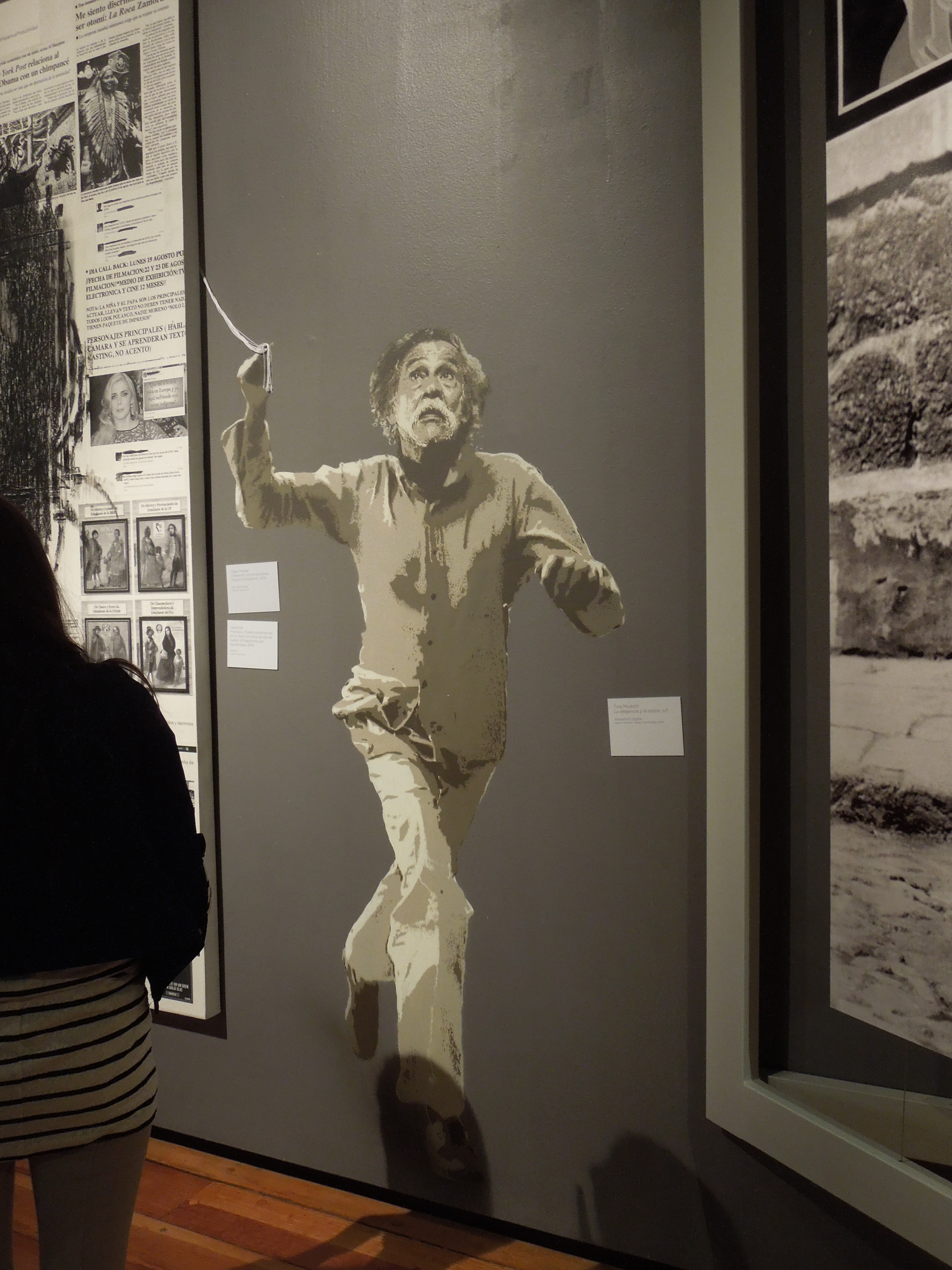

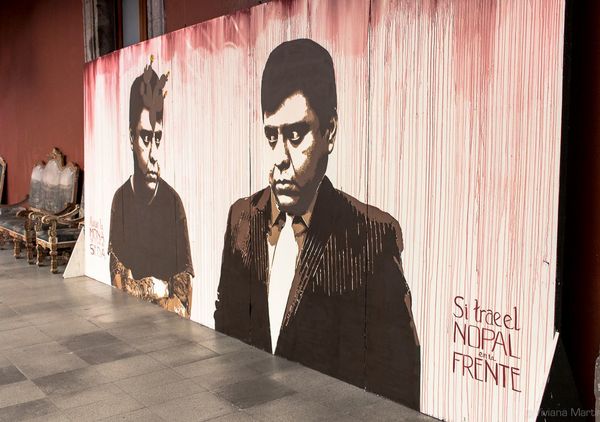

Colectivo LaPiztola, With the Nopal on the Forehead, 2016, Producciones Sta. Lucía A.C. Collection.

Colectivo LaPiztola, With the Nopal on the Forehead, 2016, Producciones Sta. Lucía A.C. Collection.