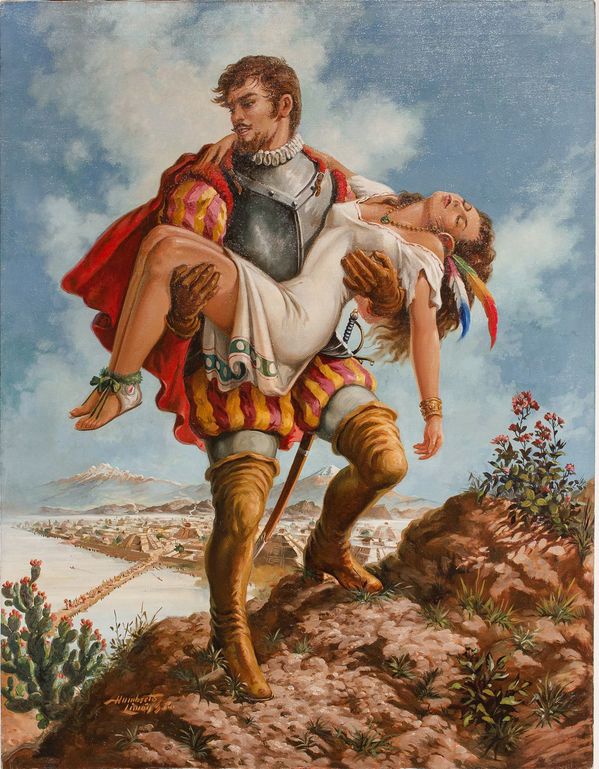

The concept of race took on such importance at the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th that the interpretation of history and society and their evolution was based around it. The way in which the foundational myth of the newborn nation was written following the Mexican Revolution of 1910 forms part of this line of thinking. As in many other parts of the world, two visions contrasted and complemented each other: one praised racial purity and considered miscegenation to have disastrous effects (which led Germany to Nazism), and the other saw miscegenation as the ideal way to elevate a race by mixing it with another that was considered to be more advanced – thus “improving the race,” as was the case in Mexico.

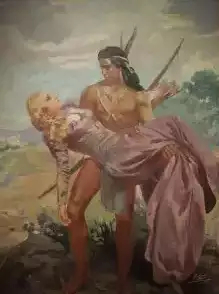

Humberto Limón, Crucible of Races, 1975, Oil on Canvas, Soumaya Museum Collection.

Humberto Limón, Crucible of Races, 1975, Oil on Canvas, Soumaya Museum Collection.

One of the intellectuals who laid the groundwork for this vision was Manuel Gamio, who advocated miscegenation as he thought that Indians were stuck in an evolutionarily-backwards stage equivalent to four hundred years in the past, and that they would only advance through a process that would make their way of life like that of the rest of the nation, which would mean leaving many of their customs and much of their culture behind in order to fully assimilate into the life of the new nation, which should be done slowly and peacefully, not like under the previous regime. The other key figure was José Vasconcelos, who also proposed a multi-stage process; for him, indigenous people possessed undeniable qualities, but he also saw them as being stuck in time and thought that it was necessary to fuse them with other races, particularly the white race, which he thought would be favorable as superior elements would absorb inferior elements, allowing “the Indian to take a million-year leap.” Even aesthetically, as he argued that the “ugliness” of Indians would slowly disappear through this racial mixture, and that if this occurred throughout the continent, blacks would also disappear, as no one would want to marry them.

Seen in this way, miscegenation was not an equalizer, but hierarchical, and once again the ‘better,’ ‘active,’ ‘superior,’ etc. attributes of the white race were exalted, while Asians, Indians, Africans and others were on the bottom, full of negative attributes or waiting to be ‘improved.’ Little actually changed from pre-revolutionary racial theories, as the end goal remained the same: the disappearance of indigenous people and the destruction of their identity in order to create a new being, representative of a homogenous nation. The mestizo had made its appearance.

Saturnino Herrán, The Legend of the Volcanoes, 1910, Triptych, Oil on Canvas, Artemio del Valle Arispe Painting Archive.

Saturnino Herrán, The Legend of the Volcanoes, 1910, Triptych, Oil on Canvas, Artemio del Valle Arispe Painting Archive.

Relative and Absolute Skin Color

The condition of the mestizo is therefore uncomfortable, as the place they occupy on the hierarchy depends on attributes such as their physical traits and, above all else, skin color. Nevertheless, skin color is relative, changing with the light, perspective, exposure to the sun and many other factors, as can be seen in the video, while its visual elements show the absolute skin tones used in Mexico City advertising and their underlying stereotypes and clichés. The column supported by those who suffer from the effects of this attests to its social weight.

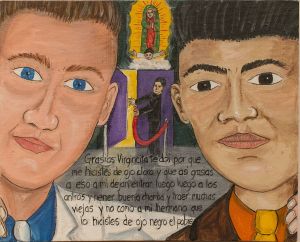

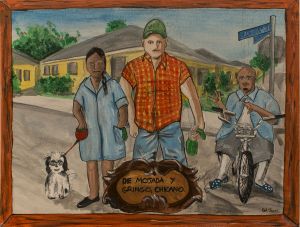

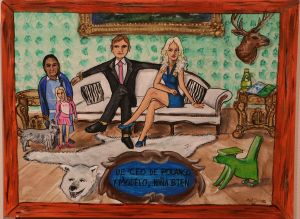

Juan Carlos “El Crayola” Pérez, Exvoto, 2005 and New Castes, 2016, Mixed Media, Author’s Collection.

Katya Gardea, The Color of My Skin, Sculpture and Video, 2016, Color Palette Prepared with Skin Tones Used in Mexico City Billboards, Stone Pillar, Resin Figures, Fashion Magazines and Marble, Artist’s Collection.

Denied Heritage

One of the most peculiar aspects of Mexican miscegenation as an identity is the disappearance of Africans and Asians from the family tree. Perhaps this is due to the prejudices that proliferated during the colonial era, persisting into independence, regarding both racial groups and the aspirations of the criollo elite to found a white nation, in which they opposed African immigration and were reluctant to allow for any non-European immigration, which lasted until the mid-20th Century, as can be seen in certain clauses of the Law on Population. To this we can add the vicious anti-Chinese campaigns in Sonora and other parts of the country, which led to the expulsion of hundreds of Asians and bloody episodes such as the massacre of 303 Chinese and three Japanese in Torreón, Coahuila in 1911.

Anonymous, Albinos and Spaniards Produce Black Throwbacks, 18th Century, Oil on Metal, National Bank of Mexico Collection.

Anonymous, Albinos and Spaniards Produce Black Throwbacks, 18th Century, Oil on Metal, National Bank of Mexico Collection.

Claudio Linati: Exoticism and Racism

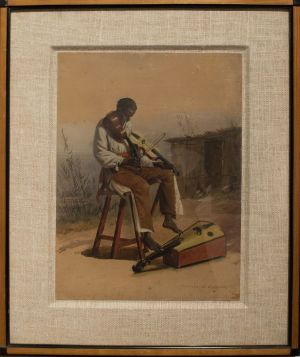

Derisive judgements of Afro-Mexicans and the gaze of exoticism centered on the use of race to explain the qualities and defects of a population can be seen in the texts that accompany the celebrated lithographs by the Italian Claudio Linati.

Edouard Pingret, Veracruz Musician, 19th Century, Oil on Paper, National Bank of Mexico Collection.Much could be said of the Jewish population, which has been fed by different waves of immigration dating back to the colonial era, when they were forbidden from settling in Mexico, as well as the many Arab communities located throughout the country, mixing with the local population and contributing elements from their own culture, which can be seen in many regions of Mexico.

Edouard Pingret, Veracruz Musician, 19th Century, Oil on Paper, National Bank of Mexico Collection.Much could be said of the Jewish population, which has been fed by different waves of immigration dating back to the colonial era, when they were forbidden from settling in Mexico, as well as the many Arab communities located throughout the country, mixing with the local population and contributing elements from their own culture, which can be seen in many regions of Mexico.

All are ethnic heritages that have enriched the country, but that have been made invisible by the myth of miscegenation between two “races,” peoples, cultures. Traces of their existence can be seen in the faces of thousands of Mexicans, as is clear in the African influence in parts of Guerrero, Oaxaca, Tabasco and Veracruz, as well as other, less-well-known areas. An identity that has been denied.

José Clemente Orozco, Woman, 1946, Tempura on Pressed Wood, INBA/MACG Archive.

José Clemente Orozco, Woman, 1946, Tempura on Pressed Wood, INBA/MACG Archive.

From Indians to Indigenous People

The diffusion of the concept of race in the mid-19th Century led to a transformation of the lexicon. The term ‘Indian’ stopped being used to refer to the existing aboriginal population and began to be used to refer to what was defined as the “pure Indian,” ancient and glorious, creating a rift between ancient and contemporary people, with the latter considered to be a degenerate population with no relationship to the former. The indigenous race, the Otomi race, the Yaqui race, the Mexican race or simply indigenous people – that is, natives of a place – were the new terms.

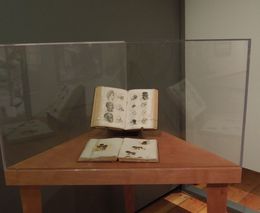

Yutzil Cruz, Mixtec Stories, 2016, Plastic Replica of a Women’s Bone, Carved Deer Bones and Aquatint. The Indigenous: A Buried Heritage

Yutzil Cruz, Mixtec Stories, 2016, Plastic Replica of a Women’s Bone, Carved Deer Bones and Aquatint. The Indigenous: A Buried Heritage

The contempt for contemporary indigenous people has cast a shadow over their real heritage, that of the family, in favor of the exaltation of the ancient Indian, a pillar of the myth of miscegenation. Yet another heritage denied. In this work, evoking the memory of her grandfather, a Mixtec speaker, the artist identifies as the granddaughter of a Mixtec and traces a history that contradicts official, hegemonic discourses, which tend to deny and bury the heritage of indigenous families.

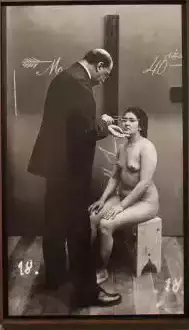

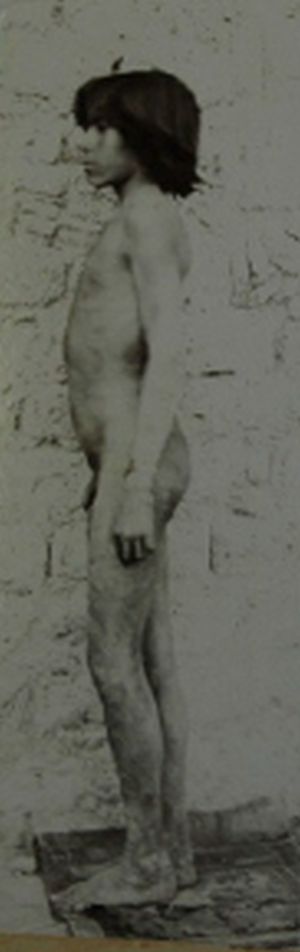

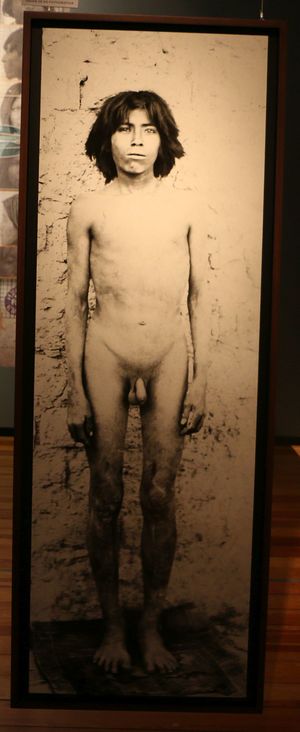

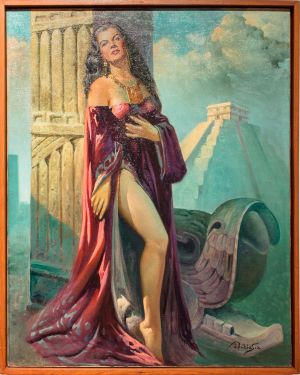

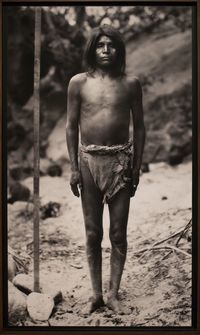

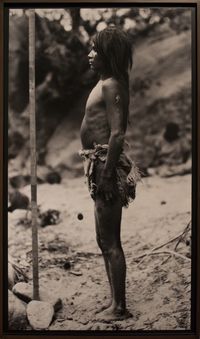

Along with these discourses, a pattern of representation was established: ancient Indians were painted and sculpted in accordance with the classical canon, like Greeks and Romans, noble and distinguished, valiant and dignified, while contemporary indigenous people were photographed like criminals, coerced, shot using unfavorable angles, objectified and submitted to measurements and other studies, using any physical or mental anomaly as proof of their degeneracy.

José Bribiesca Ruvalcaba, Woman in Chichen Itzá, ca. 1940, Oil on Canvas, Soumaya Museum Collection.

José Bribiesca Ruvalcaba, Woman in Chichen Itzá, ca. 1940, Oil on Canvas, Soumaya Museum Collection.

The revolution changed this way of seeing them: they became worth of compassion, peoples to be redeemed after the suffering and marginalization of the Díaz dictatorship.

Diego Rivera, Mayas, 20th Century, Gouache and India Ink on Paper, National Bank of Mexico Collection.

Diego Rivera, Mayas, 20th Century, Gouache and India Ink on Paper, National Bank of Mexico Collection.

And so they were represented in photographs and murals, not without a certain picturesque air, one of exoticism, giving them round forms, smooth dark skin and doe eyes. This was the style utilized by Diego Rivera when illustrating everyday scenes (a market, sowing a field, a festival) in order to recreate the past through the present.

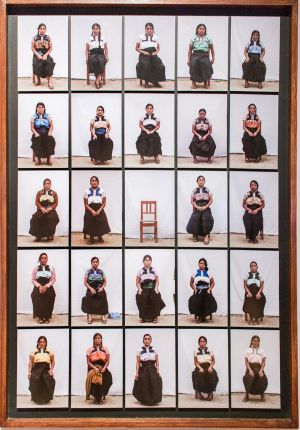

Carlos Dardón Mi vestido, mi cuerpo, mi bordado, mi piel, 2010 Fotografía.

Carlos Dardón Mi vestido, mi cuerpo, mi bordado, mi piel, 2010 Fotografía.

Concepts of beauty regarding the body, the face and the skin form part of a specific cultural context. The women of the Chiapas Highlands clearly express this in their own words, free of exoticism, insult or idealization.

Between Glory and Degeneration

Baron Humboldt recounted how, during his visit to New Spain in the early 19th Century, he was surprised to see, among the sculptures housed at the Academy of the Noble Arts, a reproduction of the Apollo Belvedere, a symbol of beauty in studies on human races. The imposition of the classical canon in the “torrid zone” formed the basis of a school that produced countless paintings and sculptures of Nezahualcoyotl as a Roman patrician, Cuauhtémoc as a Greek noble, containing none of the features or proportions of indigenous people.

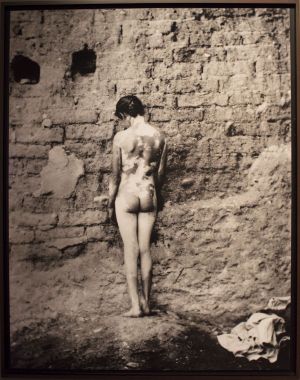

Frederick Starr, The Mottled Woman, ca. 1900, Digital Print, Smithsonian Institution Archive.

Frederick Starr, The Mottled Woman, ca. 1900, Digital Print, Smithsonian Institution Archive.

“La mirada zoológica”.

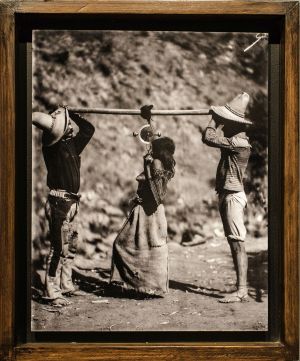

Carl Lumholtz, Anthropometric Portraits of a Rarámuri, 19th Century, Digital Print, American Museum of Natural History NY/CDI Archive, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Carl Lumholtz, Anthropometric Portraits of a Rarámuri, 19th Century, Digital Print, American Museum of Natural History NY/CDI Archive, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection. Carl Lumholtz, Weighing a Rarámuri Woman, 19th Century, Digital Print, American Museum of Natural History NY/CDI Archive, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Carl Lumholtz, Weighing a Rarámuri Woman, 19th Century, Digital Print, American Museum of Natural History NY/CDI Archive, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

These representations both accompanied and were the product of how criollos constructed a glorious past for the Mexican nation, as well as legitimizing their attempts to resolve the so-called “Indian problem” in the most sinister fashion possible: through their disappearance. More subtly but just as clearly, the idea of miscegenation promoted after the Revolution of 1910 also implied their disappearance through assimilation – that is, through the destruction of their culture.

León Diguet, Huichol Indian, 19th Century, Digital Photo Print, Musée du Quai Branly Archive, Paris.

León Diguet, Huichol Indian, 19th Century, Digital Photo Print, Musée du Quai Branly Archive, Paris.

We thus find ourselves between three extremes: the idealization of ancient Indians as a mirror of classical cultures, attempts to eliminate contemporary indigenous people or to reduce them to folklore and a miscegenation dominated by the classical canon that is difficult to recognize due to its preference for European skin color and features. It’s therefore not surprising that identity issues continue to be sensitive in Mexican society: this is fertile ground for racism.

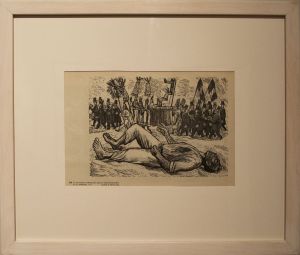

Alfredo Zalce, The Díaz Dictatorship Demagogically Praises Indigenous People, 1947, Linocut, INBA/MACG Archive.

Alfredo Zalce, The Díaz Dictatorship Demagogically Praises Indigenous People, 1947, Linocut, INBA/MACG Archive.