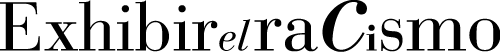

I. Conquest and Genocide, 2016, Charcoal on Newsprint on Wood, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

I. Conquest and Genocide, 2016, Charcoal on Newsprint on Wood, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.Racism – like any form of discrimination – implies a mental order and a spatial order. In the eyes of the Spaniards who explored America, indigenous people constituted an enigma: they asked themselves if they were human. Many doubted it, believing them to be closer to beasts than men. The Dominican friar Tomás Ortiz wrote that “they are incapable of learning [...] God has never created a race full of more vices [...] Indians are stupider than donkeys and they reject all progress.”

Anonymous, The Conquest of Mexico: Cortez Dismantles the Ships, The Entrance of the Spaniards to Tlaxcala, Cortez Destroys the Idols, The Capture of Cuauhtémoc and Moctezuma, Moctezuma Bends the Knee, Oil on Canvas, National Bank of Mexico Collection.

Las Casas advocated for them – “they’re inoffensive, ignorant and moderate” – while arguing in favor of African slavery, as he considered Africans to be almost animals. These apparent contradictions are due to the opinions contained in pre-existing racial classifications, in which the so-called barbarians were divided into three categories: those with strange customs but who have government and social organization, those whose language is not fit to be written and those “whose perverse customs, rough manners and brutal inclinations are like wild beasts who live in the countryside, without cities, houses, police or laws,” which included Africans and Arabs. The place that each indigenous group occupied in this classification was the subject of endless debate, as the conclusions changed depending on the interests of the moment.

Anonymous, Our Lady of Guadalupe of Mexico, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Collection.

Anonymous, Our Lady of Guadalupe of Mexico, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Collection.Another category that soon entered play was that of nobles – “only God makes them,” it was said – and the Tlaxcalan and Mexican ruling class were considered to belong to this class, giving them special rights (dressing like Spaniards, riding horses) and allowing them to keep receiving tribute, provided that they had been baptized and had completely renounced their so-called idolatry.

Unknown, Nicolás de San Luis Montañez, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Regional Museum of Querétaro Archive, INAH.

Unknown, Nicolás de San Luis Montañez, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Regional Museum of Querétaro Archive, INAH.The Spanish mental universe, which included the language, extended throughout the New World. The term “Indian” replaced the names Otomi, Nahua, Totonaco, erasing the differences between over two hundred different peoples, who were considered as if they were minors and were kept in separate congregations under the control and protection of the crown, far from the cities. The oppositions of converted Indian/idolatrous Indian, submissive Indian/rebellious and barbarous Indian, noble Indian/plebian Indian configured a network of relationships between the central government, regional powers and indigenous peoples, as well as between different indigenous groups. In the 19th Century, these categories were incorporated into the concept of race, integrated as elements of analysis with an approach saturated with racism; they are ways of classifying that have endured to this day, they are still used to determine the relationship between the powers that be and indigenous peoples.

Anonymous, Francisco Xavier de Silva, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Museum of Guadalupe Collection, INAH.

Anonymous, Francisco Xavier de Silva, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Museum of Guadalupe Collection, INAH.Population and Space in the Capital

The 1753 census gives us a panorama of the structure of the population, estimated at 40,000 individuals, of those living within the “enclosure,” or what is now the historic downtown district of Mexico City. The word “quality” was used to describe an individual’s ancestry and social status, and was described using the following terms, collectively known as “castes.”

Unknown, Layout and Description of the Quite Noble Imperial City of Mexico, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Chapultepec Castle National History Museum Archive, INAH.

Unknown, Layout and Description of the Quite Noble Imperial City of Mexico, 18th Century, Oil on Canvas, Chapultepec Castle National History Museum Archive, INAH.|

Spanish |

Criollo, Gapuchin, Spaniard, Gapuchin Spaniard |

|

Mulatto 16.7% |

Chino, Colored, Colored Slave, Dark-Skinned Slave, Quebrado, Quebrado Slave, Quebrado Freedman, Dark-Skinned Freedman, Zambo, Morisco, Morisco Freedman, Mulatto, Mulatto Freedman, Mulatto Slave, Pardo, Pardo Freedman |

|

Mestizo 14.3% |

Mestizo Castizo, Free Mestizo, Mestizo |

|

Indian |

Indian, Indian Chief, Savage Indian, Savage, Indian Vassal, Indian Noble |

|

Black |

Black Slave, Free Black, Freedman, Black |

| Filipino 0.05% |

Filipino Castizo, Chinese-Filipino, Filipino, Indian Filipino, Mestizo Filpino |

Almost half of the Spaniards were artisans, one-fifth were merchants, one-tenth were workers and the rest were servants; very few were service providers, most were bureaucrats, professors, students and professionals. Mulattos were mostly servants, one-tenth were artisans, few were service providers and a few were merchants. Blacks were almost all servants, with a handful being artisans. Half of Filipinos were servants and the other half were service providers. The Indians who lived in the city were mostly servants, one-tenth were artisans, some were service providers and very few were merchants.

Map of Mexico City and the groups that resided there in 1750, 2016 map prepared by Gerónimo Barrera based on research by Guadalupe de la Torre on 18th Century maps, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Map of Mexico City and the groups that resided there in 1750, 2016 map prepared by Gerónimo Barrera based on research by Guadalupe de la Torre on 18th Century maps, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.Colonial houses (like the one that houses this museum) constituted large, stratified spaces: the servants’ area in the back, the “noble” floor (the top floor) where the family lived, the mezzanines where offices and employees of the family business were housed, the annexes that opened onto the street where artisans and merchants primarily lived.

Multi-family colonial houses were spaces occupied by people of different “qualities”: on the top floor lived families who were more or less well off; the mezzanines and the annexes were for mestizos, mulattos and Indians, but also Spaniards who were less well off, and the other rooms were inhabited by people with fewer resources, but they could be mestizos, mulattos, Indians or Spaniards. .

This state of coexistence favored the proliferation of castes as the result of mixtures of one group with another, which contrasted with legally registered marriages, which were mostly between people of the same “quality” (Spaniards with Spaniards, mulattos with mulattos, blacks with blacks, etc.), with only 10% of them being between different social levels (Spaniards with mestizos and mulattos, very few with Indians and almost none with blacks; Indians almost always with mestizos; mestizos with mulattos and rarely with blacks; mulattos with blacks, Filipinos with mestizos and occasionally with mulattos). A spatial order that favored racial mixing, but that sought the maintenance of the social structure in order to control the population.