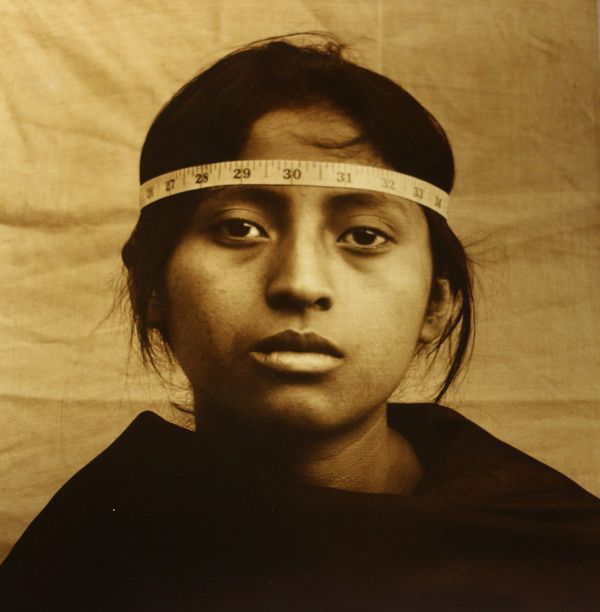

How do you determine which features define a race? By measuring, quantifying, making statistical generalizations, separating and grouping populations to give greater weight to one characteristic or another, such as skin color or hair shape. In this desire to provide a scientific basis, racial studies began to utilize special methods, instruments and instructions, giving rise to enormous inventories of nose shapes, eye colors, head sizes and brain sizes, but also of behaviors, nutritional patterns, moral and political systems and many other cultural and social traits.

Luis González Palma. The Critical Gaze, 1999, Hand-Colored Silver on Gelatin, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Luis González Palma. The Critical Gaze, 1999, Hand-Colored Silver on Gelatin, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

This data may seem inoffensive, in line with the scientific spirit. The problem is that there existed (and still exist) theories and concepts that bestow them with values, organizing the races into a hierarchy. For example, the facial angle, developed by Petrus Camper, implies the existence of a gradation between the alleged perfection of the Greek profile (100°) and that of Africans (70°), close to that of apes. Ancient Greeks were considered to be beautiful, intelligent and refined, while Africans were seen as primitive, unintelligent and ugly – in sum, their antithesis. Pure racism.

Mauricio Gómez Morin. The Quadrature of the Indigenous Mind, 2016, Wooden Rulers and Collage on Cardboard, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Mauricio Gómez Morin. The Quadrature of the Indigenous Mind, 2016, Wooden Rulers and Collage on Cardboard, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

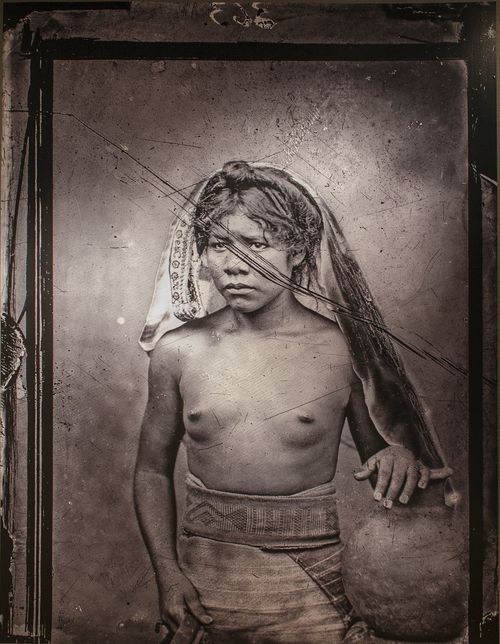

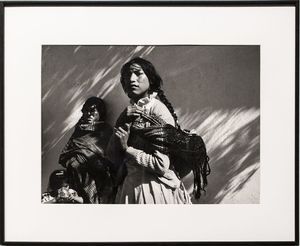

Deep down, the procedure was (and continues to be) the same: the inferiority of non-Westerners and their physical and cultural features are taken as a starting point, and are quantified and analyzed to confirm what is already taken to be true, even when the data does not support this thesis. Under this perspective, the face becomes a collection of signs with well-defined connotations, and photography – then seen as a faithful reflection of reality, producing objective images – as the ideal tool to document its characteristics: the perfect media for capturing and revealing the alleged inferiority of other races, as well as the abnormalities that persisted in the white race (in the end, these were connected, as they were both seen as either degenerations or manifestations of unevolved states of humanity).

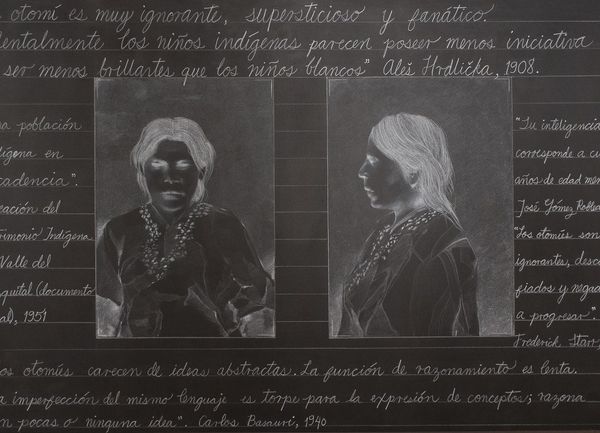

César Rangel. The Stigmatized Face, 2016, Wax Pencil and Acrylics on Canvas, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

César Rangel. The Stigmatized Face, 2016, Wax Pencil and Acrylics on Canvas, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

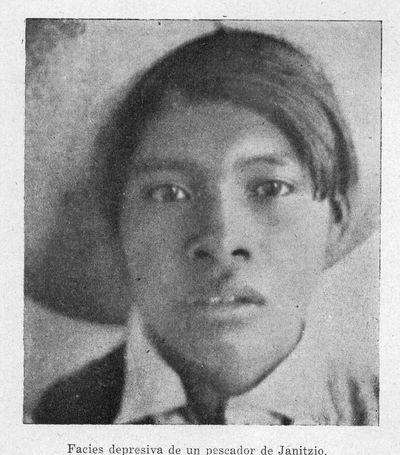

The Immobile Face

The idea that indigenous people were frozen in time, which could even be seen in their faces, is a common idea to this day, one found in news articles, documentaries and books. According to this, what could be seen in indigenous faces? Misery, abandonment, melancholy, depression, immobility, degeneration, unintelligence, fanaticism, sadness, resistance to progress, innate violence and a thousand other things, some more degenerate than others – and all of these assumptions supposedly had an irrefutable scientific basis.

Group of Eight Photos: Charles B. Lang, Bedros Tartarian and Frederick Starr, ca. 1900 Chontal Man from Tequixistlan, Chontal ;an from Tequixistlan, Chontal Man from Tequixistlan, Indigenous Boy, Huave Woman, Otomí Man, Triqui Man and Otomí Woman. Calotype. Ethnic Archive, SINAFO/INAH Archives.

The conditions in which these images were taken contributed to such interpretations: How would one stare at a completely unknown device while being pressured by soldiers? How would one not feel intimidated, not want to close one’s eyes, not move at the last second, not grimace under such tension? Anthropometric portraits – front and side, like prisoners – were not evidence of the characteristics that were ascribed to their subjects, but rather of the distrust and suspicion between the photographers and the indigenous people they depicted. Along with the overwhelming framing, the way of looking at them as if they were in a zoo, the poor lighting, the shabby surroundings and the inevitable touch of exoticism, this made these portraits into clearly unfavorable depictions, firm proof of the inferiority that they sought to capture, developed in the context of an unequal relationship that sought to perpetuate the domination of one race over another, as was said in those days.

Unknown, Young Man with Nude Torso Holding a Jar, ca. 1910. Digital Print, Ethnic Archive, SINAFO/INAH Archives, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Unknown, Young Man with Nude Torso Holding a Jar, ca. 1910. Digital Print, Ethnic Archive, SINAFO/INAH Archives, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Mariana Yampolsky, Mazahua Women, 1989, Silver on Gelatin, Mariana Yampolsky Cultural Foundation Collection.

Mariana Yampolsky, Mazahua Women, 1989, Silver on Gelatin, Mariana Yampolsky Cultural Foundation Collection.The Science and Art of the Face

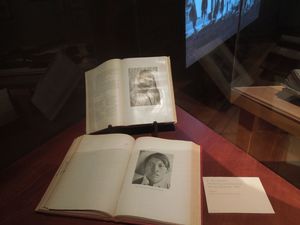

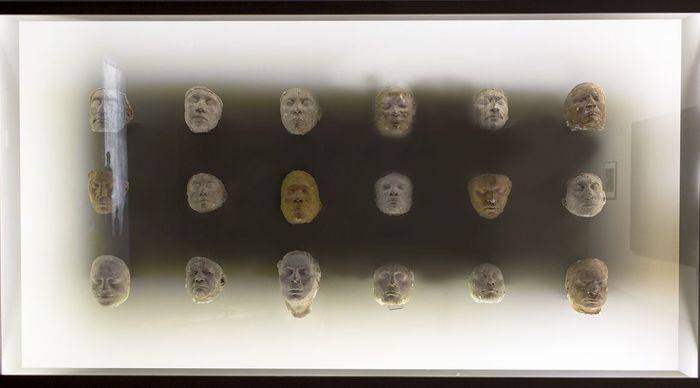

For several centuries, sculpture was seen as a faithful reflection of reality, in contrast with the more interpretive nature of painting. In the 19th Century, photography took on this role, bestowing objectivity on the world it created. Despite the desire to maximize the objectivity of “visual observations” by eliminating “personal biases” through the use of photography, as advised by experts in anthropometry, plastic casts of faces were also widely used in the study and classification of human races.

The theories that upheld that the size and shape of the head and the face revealed a person’s character and abilities – their alleged nature – were also utilized by sculptors and painters, who took casts of their models in order to subject their physical features to a detailed analysis. The case of phrenology, a discipline that enjoyed great popularity in the second half of the 19th Century, is emblematic of this.

Unknown, Casts of Indigenous Mexican Faces, ca. 1900, Plaster Collection, INAH Physical Anthropology Department, part of the collection of the National Museum.

Unknown, Casts of Indigenous Mexican Faces, ca. 1900, Plaster Collection, INAH Physical Anthropology Department, part of the collection of the National Museum.

There are enormous collections of plaster masks, many of them brought together with the goal of providing a record of people that were considered destined to disappear – the idea underlying most of the world’s ethnographic museums, in which the vibrant present of indigenous peoples was turned into their past. Among the faces we see here, we can distinguish the smile of a Chatina woman, a people who, against all such prognostics, continue to inhabit the mountains of southern Oaxaca.

The Faceless Community

Carl Lumholtz, The Pimas of Chihuahua, ca. 1892One of the most common racist clichés in Mexico is the assertion that all “Indians” look the same – the same thing is said of “negroes” and the Chinese, among others – that you can’t tell one from another. The origin of this idea lies in 19th Century theories such as mass psychology, which studied community life in non-Western societies and concluded that there was an absence of individuality, a submission to the decisions of the group and to collective forms of land ownership, a lack of will, of freedom, all of which allegedly prevented us from making out individual facial features.

Carl Lumholtz, The Pimas of Chihuahua, ca. 1892One of the most common racist clichés in Mexico is the assertion that all “Indians” look the same – the same thing is said of “negroes” and the Chinese, among others – that you can’t tell one from another. The origin of this idea lies in 19th Century theories such as mass psychology, which studied community life in non-Western societies and concluded that there was an absence of individuality, a submission to the decisions of the group and to collective forms of land ownership, a lack of will, of freedom, all of which allegedly prevented us from making out individual facial features.

video sin rostro

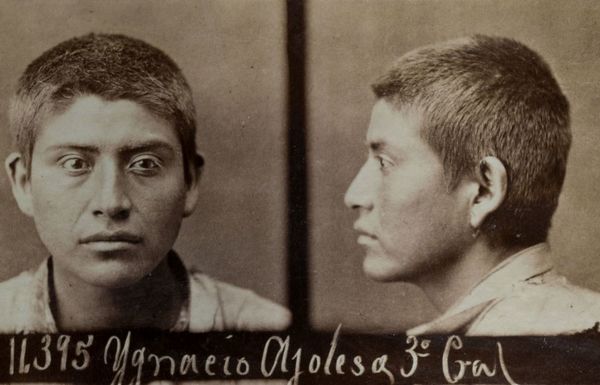

Autor desconocido Álbum de fotografías de presidiarios, s.f. Plata sobre gelatina Acervo Dirección de Antropología Física, INAH.

Autor desconocido Álbum de fotografías de presidiarios, s.f. Plata sobre gelatina Acervo Dirección de Antropología Física, INAH.

The Criminal Face

The idea that criminals are born and not made became popular during the 19th Century as social scientists claimed to have definitive proof of this hypothesis, arguing that it was even possible to identify born criminals based on their facial features and that criminal activity was due to the reappearance of primitive traits in European society, those representative of relatively unevolved races like blacks and Indians. The influence of these theories was so great that countries like the United States even incorporated it into immigration policy. The studies conducted in Mexico at the time did not escape from their influence. As many doctors and scientists took it as a given that indigenous people were primitive, whether because they were unevolved or degenerate, they felt that the behavioral patterns of ancient Mesoamerican peoples were latent or even resurgent – behavioral patterns that were considered to be bloodthirsty due to the practice of human sacrifice, a ritual that was completely decontextualized, reduced to a simple massacre motivated by mere fanaticism. “The barbarous soul of the adorers of Huitzilopochtli,” wrote Julio Guerrero in The Genesis of Crime in Mexico, an idea that was echoed in contemporary paintings and appeared, under other premises, in colonial-era art.

The fact that the prisons were full of people of indigenous ancestry, as still occurs throughout the country to this day, seemed normal in the eyes of these scientists and the ruling elite, as it did to the contemporary press. Just as the press campaigned to repress indigenous resistance to land expropriations, so it discussed the pressing need to civilize the barbarians who were opposed to the country’s “progress,” arguing that such savage peoples understood nothing but force, as their irrational and bloodthirsty nature demanded, thus justifying the wars of extermination of the federal government.

Margot Sputo, Faceless, 2016, Installation, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection..

Margot Sputo, Faceless, 2016, Installation, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection..

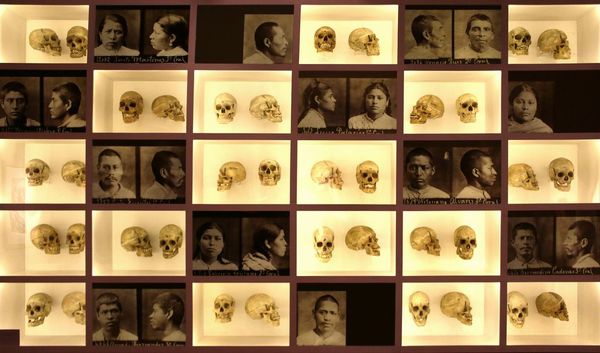

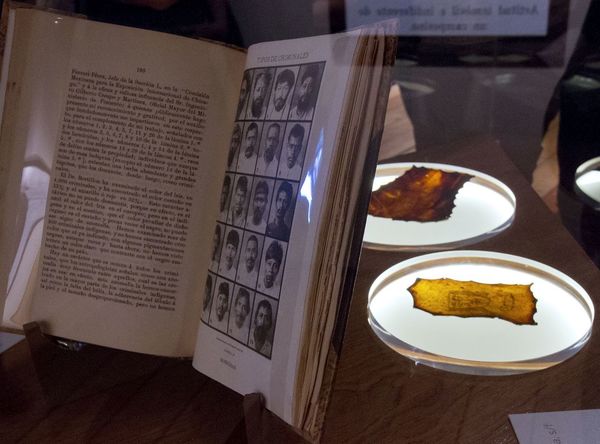

Types and Faces of Crime

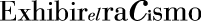

The contemporary prison system was born in the 19th Century with the construction of “modern” prisons like Lecumberri, which had medical facilities and photographic equipment for keeping detailed records on the inmates: each part of their bodies was measured, their tattoos were analyzed and, when they died, their skulls and brains were preserved, as their size, weight and shape were thought to contain the origin of their criminal conduct, connected to the “degree of civilization and perfection” of the human races.

Francisco Martínez Baca and Manuel Vergara, Studies in Criminal Anthropology, a book commissioned by the state government of Puebla for the Chicago World’s Fair, 1892, Archives of the National Anthropology and History Library, INAH. Pieces of skin with the tattoos of inmates, ca. 19th Century, Archives of the INAH Physical Anthropology Department.

Francisco Martínez Baca and Manuel Vergara, Studies in Criminal Anthropology, a book commissioned by the state government of Puebla for the Chicago World’s Fair, 1892, Archives of the National Anthropology and History Library, INAH. Pieces of skin with the tattoos of inmates, ca. 19th Century, Archives of the INAH Physical Anthropology Department.

In this same fashion, studies conducted at the Puebla prison referred to “fairly degenerate individuals of the indigenous race” (73% of the total prison population) that were “nourished with a diet that was as deficient” (they ate beans, chiles and corn, which were considered to be inferior to wheat) “as it was scarce,” concluding that “the smallness of these indigenous brains can therefore be understood, as can the reason why their absolute weight is inferior to those obtained elsewhere.”

Already convinced that “all Indians are thieves,” doctors and other scientists focused on adapting their data to this widespread saying in an attempt to prove that there was more criminal nature to indigenous people than to mestizos, criollos and Europeans, which was confirmed, from their perspective, by the fact that almost all prisoners were indigenous – regardless of the social context. For them, and for the rest of the elite at the time, this data was yet more evidence that indigenous people were an obstacle to the creation of a “civilized” society. For them to stop being indigenous was essential.

Orson S. and Lorenzo N. Fowler, Self-Instruction in Phrenology and Physiology, 1859, Book, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

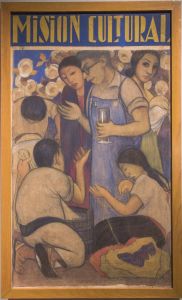

The Passive Face

The supposedly relatively young nature of the American continent led to a series of images in which American soil was more humid, its animals less developed and its men beardless, like children, ignorant of true knowledge and incapable of deciding their own fate. Those who held to this theory argued that America should be guided by Europe, which was stretching out its hand, ready to teach it the path to follow, the true religion, the proper language for expressing its thoughts and accessing education.

Alexander Von Humboldt, Europe Extends Its Hand to America, 19th Century, Digital Print, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Alexander Von Humboldt, Europe Extends Its Hand to America, 19th Century, Digital Print, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

The metaphor of the white race as the active element, as a civilizing force – fire and metal – and the other races as consisting of passive beings is a central part of racist ideology, and even has a touch of machismo, as can be seen in the interpretation of Mexicans as being the children of Malinche, as formulated by Octavio Paz in The Labyrinth of Solitude, whose pages use the adjective “passive” over and over again to refer to Mexicans. In this perspective, white people contribute, transform, emancipate, disrupt inertia and promote progress; this is the spirit of the so-called Cosmic Race. Indigenous people, meanwhile, are passive beings, stuck in time, forever tied to their land and their community as if it were a straightjacket; they have no choice but to accept the hand reached out to them that offers them a way out. To this day, many still think this way, without reflecting on the number of racist clichés that this implies.

An Ironic Gaze

Aníbal López, A Chol Photographing a Lacandón, 2016, Video, 25:36 min, Televisa Foundation Collection.

Aníbal López, A Chol Photographing a Lacandón, 2016, Video, 25:36 min, Televisa Foundation Collection.

Rigoberto Gómez Sántiz, Indifferent, 2016, Mixed Media on Wood, Author’s Collection.

Rigoberto Gómez Sántiz, Indifferent, 2016, Mixed Media on Wood, Author’s Collection.