César Rangel, Civilizing Triptych II: The Genocide of the Yaqui People, 2016, Charcoal on Newsprint on Wood, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

César Rangel, Civilizing Triptych II: The Genocide of the Yaqui People, 2016, Charcoal on Newsprint on Wood, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.In 1821, the Plan of Iguala stipulated that “all inhabitants of New Spain, whether they be Europeans, Africans or Indians, are citizens of this monarchy with the same opportunities for employment, depending on their merits and virtues,” thus laying the groundwork for equality in the newborn Mexican nation. Nevertheless, difficulties soon arose in making this a reality, as the idea of imposing a European way of life, of being, was to clash with a majority-indigenous population – what was called the “Indian problem,” an obstacle to so-called progress.

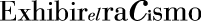

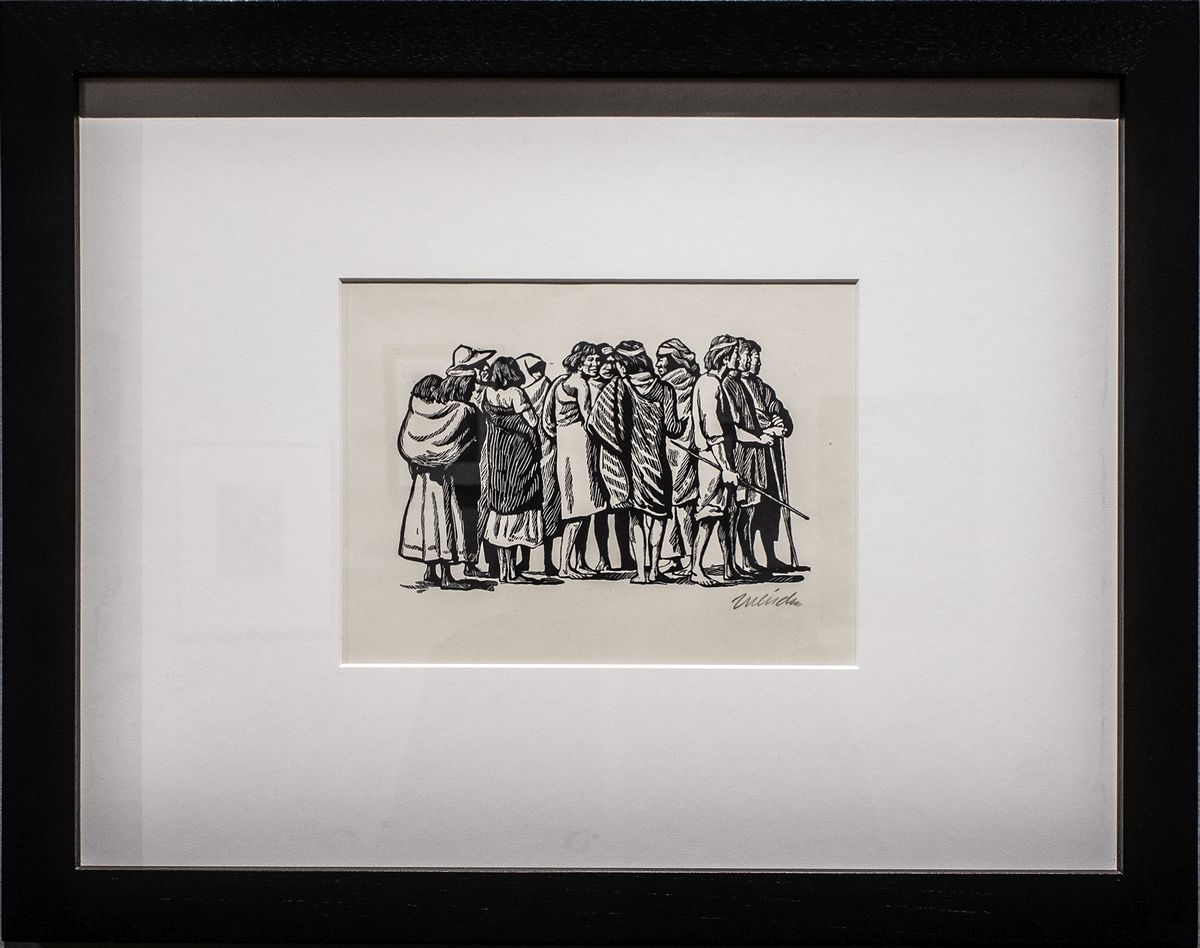

Unknown, The Indigenous Servants, ca. 1880, Digital Print, Pedro Guerra Photo Archive, FCAUADY (Autonomous University of Yucatán).

Unknown, The Indigenous Servants, ca. 1880, Digital Print, Pedro Guerra Photo Archive, FCAUADY (Autonomous University of Yucatán).In order to feed Europe’s Industrial Revolution, minerals, timber and agricultural products became sources of wealth. Indigenous people were an obstacle to the exploitation of these resources and their relationship with the government deteriorated, which can be seen in contemporary classifications: “1. Civilized Indians, who are intelligent and active, preserving their old customs and language [...] 2. Degenerate Indians [...] lazy, dirty and of crude intelligence. 3. Barbarous Indians, who are treacherous, cruel and warlike; they do not recognize authority and live on pillage.” This description was found in a geography book that was used in public schools, which also defined the white race as “the most enlightened people, those who posses the spark of vitality.”

This classification was based on the alleged nature of indigenous people, which determined their relationships with white people, whether they would obey or rebel, the latter of which was punished with war, which could become one of extermination, as occurred with the Seris, whose population was reduced to 300, and with the Yaquis. The extreme facet of racism: genocide.

Sergei Eisenstein, “Maguey,” Episode of ¡Que Viva Mexico! (1931), Film, Private Collection.

But this was not the only relationship that was formulated in terms of race, which also played a role in international affairs. Conflicts with the United States – which considered itself to be a superior race destined to dominate the rest of America – alarmed the government, which thought that the “quality” of the Mexican race was not up to the challenge, and so it promoted a campaign of European immigration, taken up by Benito Juárez himself, whose laws proclaimed that “the immigration of active and industrious men from other countries is unquestionably one of the republic’s primary needs.” The desire to construct a white nation always failed, as immigrants left for the United States at the earliest opportunity. To compensate for this, the ruling elite feverishly sought to whiten itself: it is said that Porfirio Díaz himself covered his face in talcum powder and he was immortalized in countless portraits with white skin. Santiago S. Sánchez, Allegory of the Centennial of Independence, 1909, Oil on Canvas, Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Archive.

Santiago S. Sánchez, Allegory of the Centennial of Independence, 1909, Oil on Canvas, Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Archive.

Santiago S. Sánchez, Allegory of the Centennial of Independence, 1909, Oil on Canvas, Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Archive.

Santiago S. Sánchez, Allegory of the Centennial of Independence, 1909, Oil on Canvas, Museum of the Basilica of Guadalupe Archive. Cruces and Campa, Porfirio Díaz, ca. 1870, Albumen Print, Carlos Monsivais Collection

Cruces and Campa, Porfirio Díaz, ca. 1870, Albumen Print, Carlos Monsivais Collection  Unknown, Porfirio Díaz, 19th Century, Oil on Canvas, Chapultepec Castle National History Museum Archive, INAH.

Unknown, Porfirio Díaz, 19th Century, Oil on Canvas, Chapultepec Castle National History Museum Archive, INAH.The Genocidal War Against the Yaqui

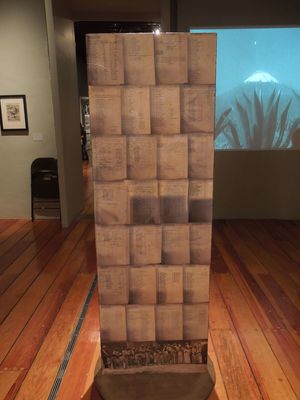

Bounded by two rivers, the Yaqui and the Mayo, the homeland of the Yaqui people was particularly envied for its fertility. Their refusal to give it up led to many rebellions, leading the government to launch a war to “pacify” the area, to “civilize the savages,” which concluded with their almost total extermination and the deportation of thousands of Yaquis to different corners of the country, with many of them sent to Yucatán to work as slaves on henequen plantations. It’s estimated that, between 1880 and 1910, the Yaqui population of Sonora dropped from 25,000 people to 3,000. The lists of deportees bear witness to this atrocity: they contain many women and children, the latter of whom were turned over to Hermosillo families, with the idea that, working, they would become civilized. The stele made up of these historic documents pays homage to their memory.

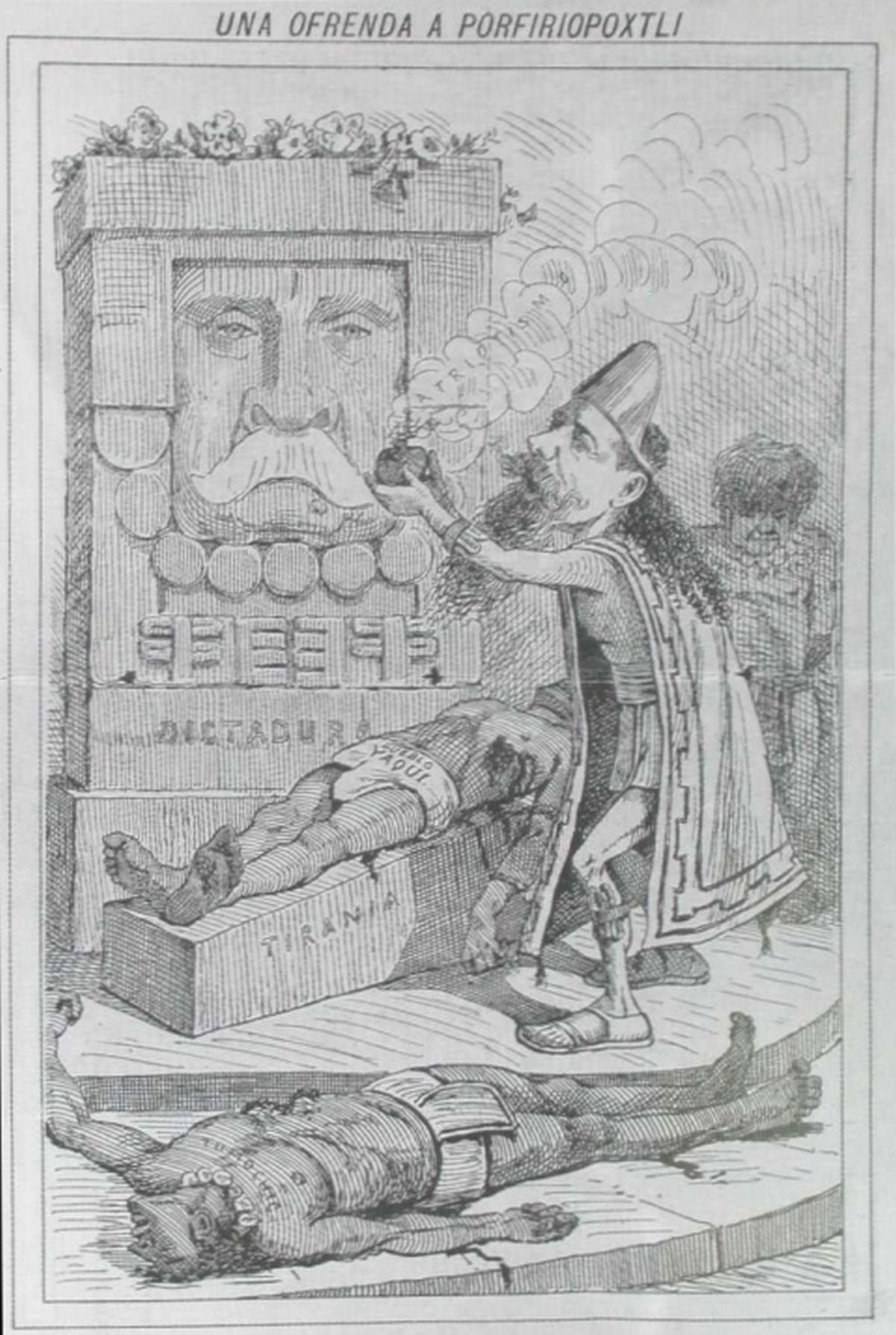

Unknown, “An Offering to Porfiriopoxtli” in El Hijo del Ahuizote, Vol. XV, No. 731, April 29, 1900, Print, National Anthropology and History Museum Archive, INAH.

Unknown, “An Offering to Porfiriopoxtli” in El Hijo del Ahuizote, Vol. XV, No. 731, April 29, 1900, Print, National Anthropology and History Museum Archive, INAH.

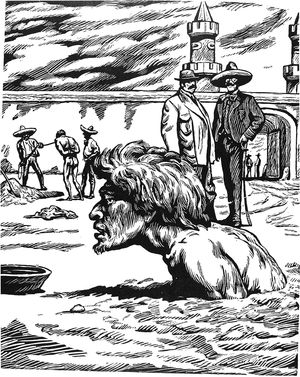

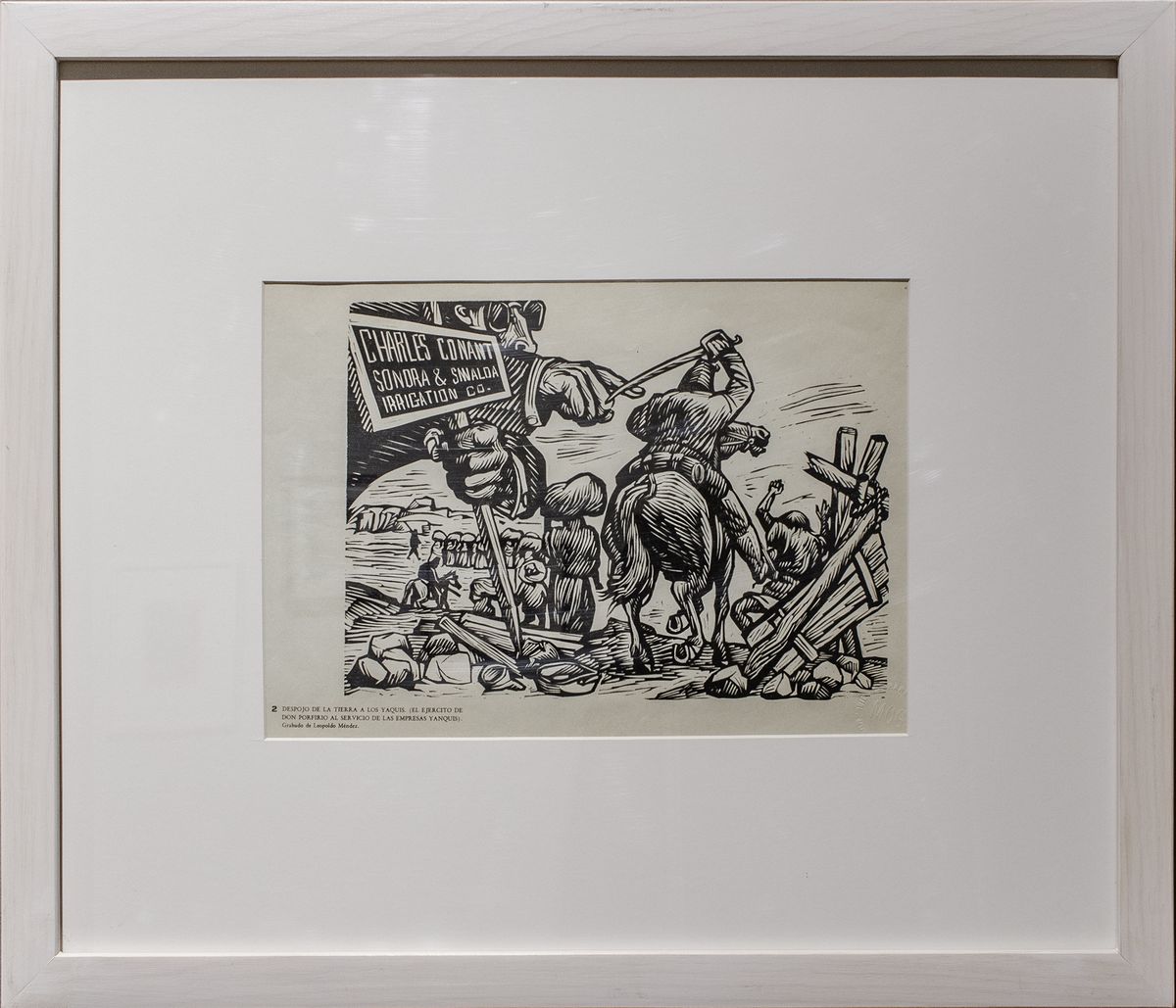

Leopoldo Méndez, Seizure of the Yaqui Lands (Don Porfirio’s Army at the Service of Yankee Business), 1944, Linotype, INBA/MACG Archive.

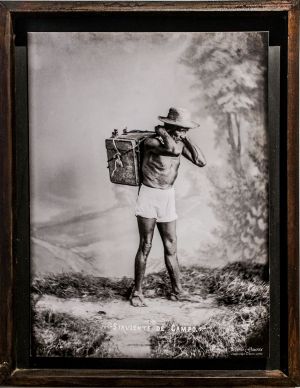

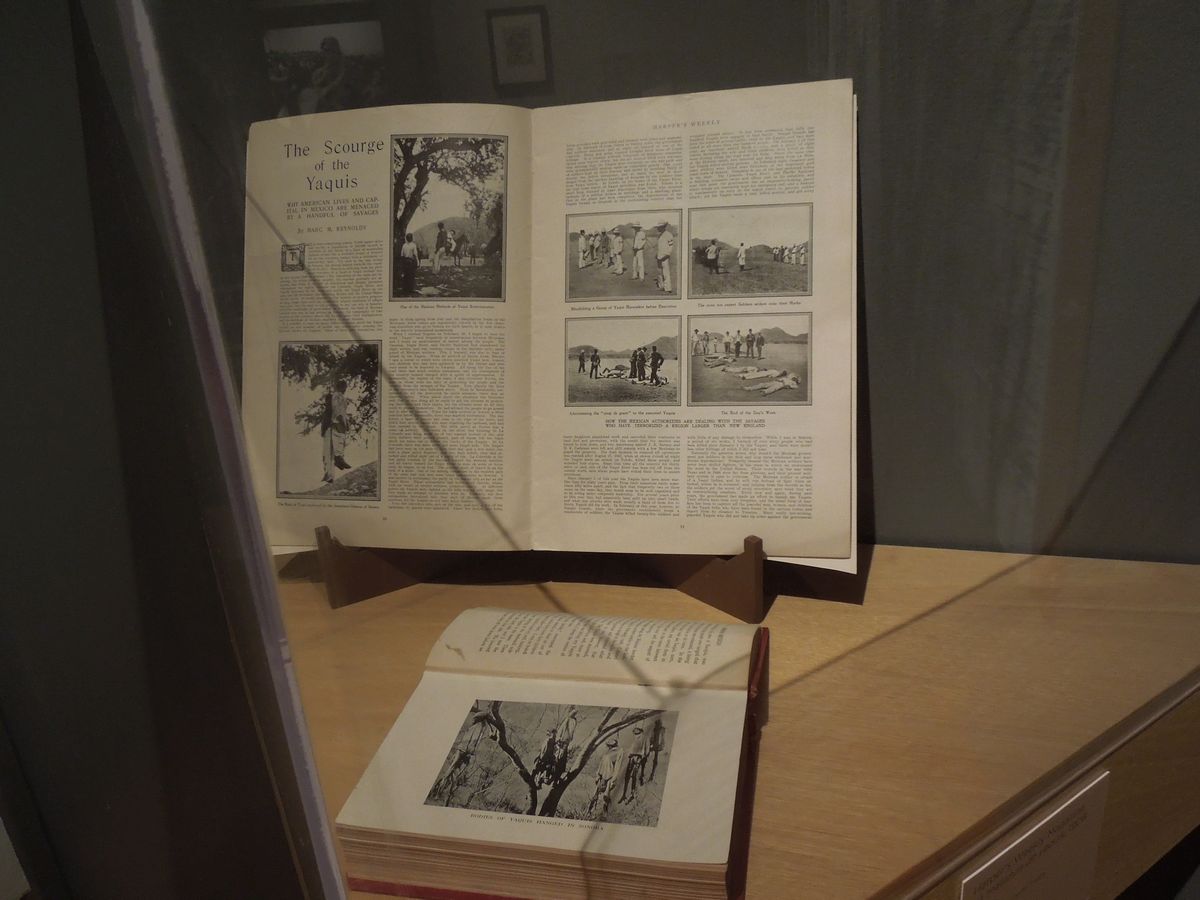

Leopoldo Méndez, Seizure of the Yaqui Lands (Don Porfirio’s Army at the Service of Yankee Business), 1944, Linotype, INBA/MACG Archive.  John Kenneth Turner, Barbarous Mexico, 1912, Book, César Carrillo Truba Collection. Harper’s Weekly Magazine, The Scourge of the Yaquis, 1908, Magazine, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

John Kenneth Turner, Barbarous Mexico, 1912, Book, César Carrillo Truba Collection. Harper’s Weekly Magazine, The Scourge of the Yaquis, 1908, Magazine, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.

Mauricio Gómez Morin. Deportation and Extermination of the Yaqui People, Memorial, 2016, Official Lists of Yaquis Deported to Different Parts of Mexico, Archival Photographs, Wooden Stele with Dirt from the Sierra del Bacatete, Sonora, César Carrillo Trueba (Facultad de Ciencias de la UNAM) Collection.